In this corner of the WorldWideWeb, we publish contributions that consider the literary view on energy and on the energy transition. We assume that the success of the energy transition is highly dependent on society's exploration and understanding not only of its technical, economic and legal aspects. Therefore, it is only logical that we provide a stage for the intersection of literature and energy. Here, literature and art can provide information through stories, images and the way in which they emotionalise and create value. So far, we have initiated an encounter between renewable energy and visual art (especially in the form paintings) in related projects such as ‘Energy meets Art’. Here, now, is where literature and energy meet.

In the future, we will showcase past and present texts and authors capturing our handling of resources in stories with a particular focus on electricity. Completely different questions and subjects may surface. For example: what does literature have to say about how different forms of energy can characterise and have characterised living environments and communities? Looking at the past shows us that cultures change along with the energy sources which they exploit. The 19th century was the age of coal, the 20th century was also driven by oil and uranium. What these evolutions meant for the living and working environments and how they have changed the cultural and natural landscape is very vividly reflected in literature. It shows which hopes and fears, which ideas on future and progress are intertwined with energy. And naturally, it is also a seismograph for the changes arising from today’s energy transition and the new solar age. In other words, the energy transition is also a ‘cultural transition’, and literature can provide information about this process through a high-resolution lens.

Another question can be asked: which heroines and heroes does literature invent where progress in energy matters is concerned? Are there for example characters that have acknowledged the ecological need to curb climate change and at the same time see the energy transition as an opportunity for participation, for a region and for an actual joint effort? Are ethical stances developed and framed that may inspire the reader?

Here, we will not be able to offer comprehensive answers to such questions, which ultimately arise from the highly complex relationship with our resources. Yet often even a glance on the art and their stories has the effect that one views everyday familiar things in a different light. Art prefers to peel away the self-evident, skilfully shifting perspectives; one almost always learns something new about one’s own time and the opportunities that surround one’s own actions. The fact that there are few things that are more common and familiar to us than electric current can only mean that we can discover a lot more about it; as long as it flows not only from the socket, but also from the page.

Initially, we should proceed more or less chronologically and cursorily: we will start with the beginning of the scientific age in the 1800s. Next, we take a look at the energy-related literary pages of the industrialisation in the 19th century and the ‘petrofiction’ of the 20th century. We arrive at the 'Renewable Stories' of our present time and some visionary blossoms of the energy transition: ‘Solarpunk’ takes a look at the future...

Across the ages, the subjects of energy and electricity have quite frequently caused a literary resonance and created a network all of its own; let’s take a look!

Take-off – The Great Experiment

The literary and cultural take-off of electrical energy can be described with two words: ‘experiment’ and ‘Romanticism’! This gives rise to at least two questions. Firstly: did one not already know the phenomenon much earlier? Secondly: wasn't the Romantic era characterised by scepticism towards progress and scientific enlightenment? The first question can be answered affirmatively: the Ancient Greeks already knew the electrostatic charge, which they generated using amber. It was at this time that the word electron was first phrased, with which the Greeks meant nothing more than the sunny yellow amber itself. And of course, people already knew about lightning and the infamous electric eel. The great time of the scientific discovery of electricity, however, only starts much later, more particularly in the decades after 1750. A prominent date is the year 1790, when Allessandro Volta (1745-1827) and Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) discovered that electrical charges could be used to move frog legs.

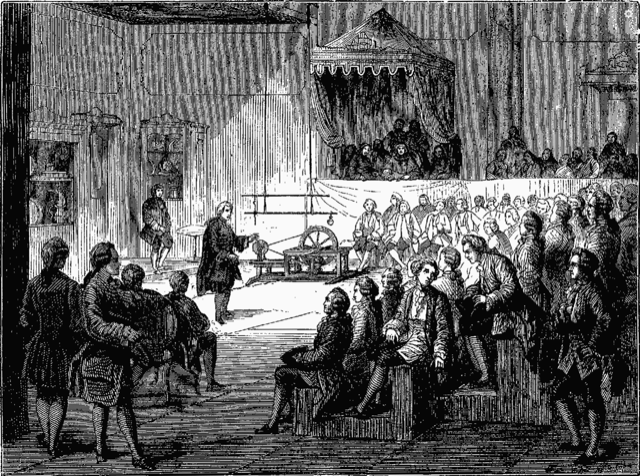

The answer to the second question regarding the characteristics of Romanticism, however, is no: the Romantics were industrious natural scientists and Galvani’s frog experiments had something to do with this: observing the effect of electricity on living creatures left people with the staggering suspicion that the Secret of Life had been discovered. Is electrical current life itself? Is it the living force and is death therefore no more than an individual power outage? This conundrum drove the Romantics and they began experimenting on a grand scale. Some of these experiments could take place as cultural gatherings: they were not seldom organised as soirées for wealthy spectators seeking out the spectacular. One must nevertheless add that this took place before or during the earliest emergence of the technical sciences: at this stage, electricity was often still studied by researchers working within the model of universal scholarship; they could therefore be philosophers, natural scientists from various fields, writers and even politicians or diplomats.

During this period, electricity only appears in one particular practice: the experiment. We already mentioned Galvani. Another famous name is Johann Wilhelm Ritter (1776-1810). The electricity pioneer conducted research in Jena and went quite far, or rather too far in his ardour for the new science. Ritter locked himself up in his laboratory for days at a time, worked manically, consumed massive amounts of alcohol and stimulants, neglected his family and spent his life savings on experiments and lab equipment. He especially carried the notion of the experiment too far: he electrified himself, and applied current to his hands, tongue and eyes (among other things) to explore the effects of different charges. He died young, in part due to his extreme methods. In the process, he also devised a technical artefact that is once again the focus of research in our present energy transition: the battery.

Ritter was a genius autodidact who very quickly acquired high scientific acclaim, like Alexander von Humboldt, Goethe and Novalis. (By the way: Central Germany was definitely the early centre for electricity.) Novalis in particular was inspired by the ideas and discoveries of his friend Ritter. He once expressed his admiration for the exceptional researcher in a beautiful play on words: “Ritter is a knight, and we are mere squires”, alluding to Ritter’s surname, meaning ‘knight’.

Novalis (1772-1801) is one of the many authors of this time, who transferred the newly discovered phenomenon from the experiments and laboratories to literature. In his most famous text, the novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen, we encounter the character of Klingsohr, who, during a convivial and festive evening and in the flow of stories and drinks, puts forward the idea that electricity is that all-pervading vital force. In his account, gold, iron and zinc are used to perform a number of electrically supported resurrections using a galvanic reaction, for instance of the giant Atlas: when the chain was closed, “a flash of life quivered in all his muscles. He opened his eyes and stood up quietly.” A similar thing happens to the princess Freya, who is also reawakened using galvanic know-how: “There was a sudden violent stroke. A bright spark leapt from the princess.”[1] Even if in Freya’s case, a kiss from the hero is still needed to complete the resuscitation, it would not be too far-fetched to see a sort of historic science fiction in these scenes: for instance, a forerunner of the medical emergency care that everyone knows today, even if only from the silver screen: the defibrillator, a current-based shock generator that makes hearts beat again.

Moreover, Klingsohr’s account is a fairy tale full of complex allusions and whimsical metaphors. It is a text whose strong allegorical charge is not necessarily easy to follow, but it is precisely for this reason that it is exemplary how electricity pervaded the literary summits of that time. Jean Paul, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Achim von Arnim, Kleist and Goethe: the first group of authors of the so-called genius era was a playground for electric charges.

Goethe again: in 1825, having already reached the age of seventy-six years, the poet writes an essay on weather theory, featuring the following opulent thought: “Electricity is the pervasive omnipresent element which accompanies all material existence, as well as the atmosphere; it can be imagined impartially as the soul of the world.”[1] There are two things worth noting about the panoramic view that this quote gives on electricity: firstly, he links energy to atmospheric forces and weather phenomena such as wind and water, bringing him quite close to those 'diluted' but almost omnipresent energies that are being rediscovered by the current energy transition. Secondly, one notes from the embellished tone that electricity is still a phenomenon to be discovered. This clearly shows the contrast with our present day: electricity is universal and omnipresent, but it is anything but self-evident.

Concise maxims for today's most effective and sustainable use of electrical energy could only be derived from this view over the ages with some difficulty. From a historical distance, one aspect of this view is nevertheless very clear: it shows how variable and multifaceted our handling of the resource is. Electricity and energy are not phenomena whose applications and meanings are fixed, but change with our technologies, habits and appreciations.

[1] Free translation

Literature

- Johann Wilhelm Ritter, Fragmente aus dem Nachlasse eines jungen Physikers, hg. v. Steffen u. Birgit Dietzsch, Verlag Müller & Kiepenheuer, Hanau 1984.

- Novalis, Heinrich von Ofterdingen, 1800, any edition.

- Johann Wolfgang v. Goethe, „Versuch einer Witterungslehre“, in: Goethes nachgelassene Werke, Cottasche Buchhandlung, Tübingen u. Stuttgart 1834, S. 247-282.

Research recommendations

- Michael Gamper, Elektropoetologie. Fiktionen der Elektrizität 1740-1870, Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2009.

- Jürgen Daiber, Experimentalphysik des Geistes. Novalis und das romantische Experiment, Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001.

- Katrin Schumacher, „Der ‚wunderbare Sinn‘ zwischen Experiment und Text. Anmerkungen zur Organisation eines Feldes der Un-/Sichtbarkeiten um 1800“, in: Aurora. Jahrbuch der Eichendorff-Gesellschaft (Naturwissen und Poesie in der Romantik), Bd. 64, Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 2004, S. 1-20.

- Bernhard Siegert, „Currents und Currency. Elektrizität, Ökonomie und Ideenumlauf um 1800“, in: Jürgen Barkhoff (u.a.) Netzwerke. Eine Kulturtechnik der Moderne, Böhlau Verlag, Köln 2004, S. 53-68.

“Under this half daylight...” – Energies of industrialisation

Electrification and experimentation: the 18th century cautiously approached the mysterious ‘life force’ of electricity and integrated it in philosophical and artistic concepts. However, despite a few medical applications, electric current was not an energy source for practical uses; and outside the entertainment sector, such as electricity shows and spectacles, not a commercial commodity either.

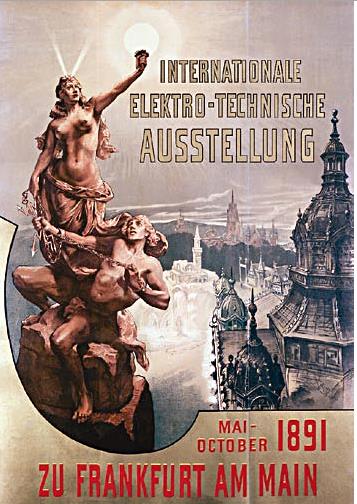

In the 19th century, this tentative approach would be abandoned. The industrialisation discovered the phenomena, incorporated it into its technical processes and promoted and marketed it with an intensity that has been unrivalled even to this day. It’s at this time, too, that the vocabulary with which we are all familiar today pops up: power and electricity plant, generator, dynamo... Electrical energy is far from being self-evident in the 19th century, but the process in which it becomes a cultural driver accelerates rapidly. If in the 1800s it was a speculative variable, in the 1900s it becomes an engineering one; where erstwhile it soared metaphysical heights, in the 19th century it touches ground for the first time with electrical lines, first for telegrams, later also for high voltage current. On 25 August 1891, the first three-phase current transmission across 175 kilometres from Lauffen to Frankfurt represents a key achievement for the unprecedented optimism displayed by the engineering culture.

Wherever electrical energy flows, the ‘new age’ begins, as progress and future have shown. Or more succinctly: electricity is modernity.

However, before this idea was accepted, a different energy system would dominate the social debates and spark the literary imagination: coal-fired steam power. For the sake of tradition, the symbol of this energy transformation is derived from Antiquity: Prometheus, the mythical and literary ‘bringer of fire’, to whom humanity owes new ways of life and creation. The transformation was noticeable in many places, nevertheless the prevalence of this new technology was nowhere as tangible as in the field of transportation and its infrastructure: steam ships and steam trains open new paths and become part of the landscape, cities and folklore. In other words: even the heroines and heroes of 19th century literature are exposed to this great leap forward. One inevitably encounters them inside these modern means of transport; travel is frequent and ever swifter. That the fossil culture is already sawing off the branch on which it is sitting, is shown by one of the greatest visionaries of the steam era: in Jules Verne’s (1828-1905) Around the World in Eighty Days, published in 1873, the notoriously hurried Phileas Fogg burns large parts of his wooden steam ship due to a dramatic shortage of coal in order to cross the Atlantic and still arrive in London on time.

Probably the most monumental artistic testimony of any shift in energy and transportation in the fossil age, however, is a painting: in vibrant colours, English painter William Turner (1775-1851) depicts the final stretch of the Fighting Temeraire. The tall ship HMS Temeraire (HMS being short for “Her or His Majesty’s Ship”) was a proud three-master that achieved great notoriety in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Here, it is being tugged to its final berth over the Thames by a much smaller, unnamed and far less majestic steamboat. This is the last stretch for this elegant wind-powered vessel, painted against an energetic and glowing red sky. The French scientific historian and philosopher Michel Serres dedicated an instructive text to this Turnerian scene that is just as beautiful. Entitled Turner translates Carnot, Serres bridges the gap between art and physics: William Turner, the early impressionist painter and Sadi Carnot (1796-1832), the physicist behind thermal engines are both portrayed by Michel Serres as protagonists of the thermodynamic age, as the focus is no longer on the relationships between stable objects, but on intensities and the lively hustle and bustle of undefined phenomena (such as steam and clouds).

What’s more, in 2005 Turner’s picture was chosen as Britain’s greatest painting in a BBC survey, which incidentally shows how central a position the subject of energy takes in a nation’s cultural memory. Another recent flash of Turner's picture testifies to this: in 2008 it gave the James Bond series a shot of art-historical elegance. In Skyfall, the slightly haggard muscle man Bond (Daniel Craig) and the clever tinkerer Q (Ben Whishaw) are sitting on a bench in the London National Gallery, in front of Turners painting. The Fighting Temeraire once more comes into play as a hint to a change in time and energy, but this time it is the explosive fighting machine Bond, around whom it has become a bit lonely, while the delicate Q has since long performed the agent job with networked and smart energy. The age of digitised energy is forthcoming here as well, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

But let’s get back to the old forms of energy that were new in the mid nineteen hundreds and were considered a guarantee for progress. When the euphoria of the ‘marriage between water and fire’ reached the literary world, it produced remarkable testimonies such as poems about technology and machinery. Worth mentioning is Theodor Fontane’s (1819-1898) four-stanza poem Lord Steam (Junker Dampf) written in rhythmic alternate rhyme, published in 1843 in the magazine ‘Die Eisenbahn’. As one can suspect from the title, the poem is somewhat curious. It deals with the new forces that can only develop their potential in a tamed and domesticated form - that is, with the use of technology, or, as Fontane says, in the "dungeon kettle" - and can then be used as locomotives, for example. The fourth stanza of Lord Steam goes as follows:

And thus, despite his bonds of metal

Fastened still to foot and hand,

He carries away the dungeon kettle

On his flight across the land,

Rooting up the rows of houses

On his rampaging foray,

Until once more he’s in the open

Wilderness, a child at play.[1]

This culture of fire, steam, rivets and pipes is currently undergoing an aesthetic revival in the neo-Victorian imagery and fashion of so-called Steampunk. – A phenomenon that when considered from our current point of view, being the second solar age, already puts the fossil era at a considerable historical distance, as it only appears ‘in costume’, romanticised in an equally fantastical and glorifying manner. Another poet, Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), is staying in Paris when the steam-powered transportation shift is taking place. He describes it in 1843 (the same year as Fontane) in one of his Lutetia reports on politics, art and way of life for the Augsburger Allgemeine Zeitung, as follows:

The opening of the two new railways, one to Orleans and one to Rouen, causes a shock that is felt by all [...]. The entire population of Paris is currently forming a chain in which the electrical spark jumps from one to the other.[1]

As can be seen, the text appropriates terms from the domain of electrical phenomena. This metaphor paints the image of the start of an era while evoking quite ambivalent thoughts and sentiments. According to Heinrich Heine, an energy transition equals a change of era:

We barely notice that our entire existence is dragged and hurled onto a new track, that new relationships, joys and hardships await us, and the unknown works its unearthly charm, tempting and terrifying in equal measure. This must be how our forefathers felt when America was discovered, when the discovery of gunpowder was announced by the first shots, when the printing press sent the first pages of God’s word out into the world.[1]

Soot: considered with the sobriety of history, the age of coal-driven industrialisation was a dark time. Dark with regard to the misery of large parts of the population in the industrial cities and their unimaginable working and living conditions. Dark also in the literal sense, as the natural light was veiled by soot. This is how railway and England traveller Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) described his visit to Manchester.

A sort of black smoke covers the city. The sun seen through it is a disc without rays. Under this half daylight 300,000 human beings are ceaselessly at work. A thousand noises disturb this damp, dark labyrinth [...].

Today, this soot from the industrial chimneys can still be found in core samples of Alpine glaciers and as we’ve since long known, the ‘historic’ environment already responded in a striking manner as well, namely in its evolutionary colour developments, to the changes in the air and the constant twilight of the industrialisation. The so-called industrial melanism signified an impressive change, mainly in the population of peppered moths, a species of moth whose number of bright specimens dropped significantly in the soot-covered industrial regions of 19th century England. Conversely, the number of dark forms now rose, as they found much better cover on the blackened surfaces of their habitat. It is not least this massive influence on the environments and living areas that led to wide-ranging deliberations about alternative forms of energy in the late 19th century and brought a known player back to the fore: electricity.

[1] Free translation

Literature

- Jules Vernes, Around the World in Eighty Days, 1873 (any edition).

- Michel Serres, „Turner übersetzt Carnot“, in: Ders., Über Malerei, aus dem Französischen v. Michael Bischoff, Merve-Verlag, Berlin 1992, S. 89-109.

- Theodor Fontane, Junker Dampf, 1843 (any edition).

- Heinrich Heine, „Lutetia“, 2. Teil, LVII, 5. Mai 1843, in: Ders., Sämtliche Werke, 6. Band, Vermischte Schriften, II Abteilung, John Weiß-Verlag, Philadelphia 1856. Furthermore: http://www.heinrich-heine-denkmal.de/heine-texte/lutetia57.shtml

- Alexis de Tocqueville, „Notizen über eine Reise nach England“ (1835), in: Wilhelm Treue u.a., Quellen zur Geschichte der industriellen Revolution, Musterschmidt-Verlag, Göttingen 1966, S. 128.

Research recommendations

- Christoph Asendorf, Batterien der Lebenskraft. Zur Geschichte der Dinge und ihrer Wahrnehmung im 19. Jahrhundert, Anabas Verlag Gießen 1884 (zgl. Weimar, Verlag und Datenbank für Geisteswissenschaften 2002).

- Michel Serres, Hermes III. Übersetzung, übers. v. Michael Bischoff, Merve Verlag, Berlin 1992.

- Prometheus. Menschen, Bilder, Visionen, Eine Gemeinschaftsproduktion des Deutschen Historischen Museums, Berlin, und der Stiftung Industriekultur, Völklingen Saarland, Dokumentation, hg. v. Rosmarie Beier 1998.

- Philipp Frank, Theodor Fontane und die Technik, Verlag Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2005.

- Götz Großklaus, Heinrich Heine. Der Dichter der Modernität, Wilhelm Fink Verlag, München 2013.

Eddies of light

Collecting and citing the many applications of electricity and its artistic testimonies by the end of the 19th century would be a task without end. It is the largest and most extensive innovation of this time, creating new imagery and views, especially as its first and foremost appearance is in the form of light. Electric lighting began to change the character of streets and cities: illuminated signs, street lighting and brighter inside lights, for instance in stores and restaurants, started spreading. At first, this new form of energy is only available to those who can afford it.

French novelist Marcel Proust (1871-1922), for instance, recounts a summer in one of the mundane coast towns of Normandy. Balbec is the name of the town mentioned in his In Search of Lost Time, which he based on the actual coast town Cabourg, with its larger-than-life grand hotel and a beach promenade with hazy impressionist views of the English Channel. Every now and then, the novel’s narrator does not look out towards the sea and its appearance that changes with the weather and the time of day, but rather inland. One evening, the scenes in the hotel restaurant are revealed, bathed in electric light. The dining hall and the social life therein appear like a high-society luxury aquarium, not without a hint of mockery and a feel for the grotesque. The electricity creates “eddies of light” in the room: “an immense and wonderful aquarium against whose wall of glass the working population of Balbec, the fishermen and also the tradesmen’s families, clustering invisibly in the outer darkness, pressed their faces to watch, gently floating upon the golden eddies within, the luxurious life of its occupants.”

The peculiar thing about the innovation of electricity, however, is that its almost democratic and collective character is already recognised relatively soon after its introduction. This is based on elementary physical and technical properties: electric current, and more precisely alternating current, is relatively easy to divide, transmit and distribute. Inherent to current is that it flows; not in closed-off aquariums, but in the public space, in other words in fanned-out and branching grids. Especially because of these properties, electrical energy is acknowledged as an alternative to the very stationary and static steam power. The star of coal-fired steam machines had sunk again quickly after its euphoric rise at the start of the century. The main cause for complaints was a technical disadvantage: apart from transmission shafts, distribution was not possible. The room for steam power in principle remained the production room. Contemporary witnesses therefore described the highly concentrated force as a vehicle possessed by few; the exploitative character of early industrialisation was thus already present in its technical infrastructure.

The second disadvantage: the already mentioned pollution. The early 19th century had had its fill of smoke and soot.

Electricity as clean and distributed energy, by contrast, represents an energy transition and the path towards a second, more gentle phase of industrialisation. Looking at this historical innovation process, similarities with our present day are striking, as the properties are mentioned that also characterise our current energy transition. The fact that renewable energy is cleaner (especially compared to coal), is self-evident; however that the concept of decentralisation is experiencing a renaissance is also worth noting. Today, this signifies the generation and storage of electricity by many small, geographically spread installations. At the time, one discovered the advantages of decentralisation at the other end of the distribution chain: it concerned a wide-scale and affordable supply and use of electricity, for instance the possibility to operate electric motors in smaller workshops, so that manual labour was offered greater opportunity in the hard competition with large centralised steam-powered enterprises. Although the two energy transitions occurred during very different periods, it is striking that clean and innovative energy, both then and now, is not an exclusive commodity, but creates a manner of joint venture in which a democratic and civil-society spirit of undertaking is manifest.

Meanwhile, another question remains: from which sources and by which power plants was electricity ultimately produced around 1900? One relatively quickly switched to coal-fired generation of electricity and as such set the course for the centralised energy system of 20th century. Nevertheless, there was also a pioneering phase, during which hydropower in particular was planned and experimented with. Thus, the use of eco-power was certainly deliberated by the people of those days: the rivers of the Alps, for instance, are energy suppliers that make alternating current flow into the German lowlands (according to Oskar von Miller). The idea of green electricity is therefore over a hundred years older than one might think.

Democratic, decentralised, clean: with these accents, electricity became the driver of a gentle modernisation. Noteworthy is the symbolic side of this project, as it is aggressively endowed with feminine imagery and allegories. The first one worth mentioning is a character whose ancestry can be traced back to the realm of fairy tales. Here name is taken from French: la fée électricité; here, in its form of a fairy, the mysterious character of electric current and its swift flow, crossing space in a flash, on one hand, is combined with the promise of progress and hope for a future free of austerity and worth living on the other hand. The fée électricité is the model for the many allegorical characters of any energy transition, appearing on posters and frontispieces. They are all heroines in a noble, bright and idealised appearance. They are often used to advertise electricity exhibitions or electrification projects; this incidentally shows that electrical current already had acquired the status of a commodity.

Not seldom does electricity appear in some sort of antagonistic duet, namely in juxtaposition with, or better yet, in confrontation with Prometheus, her male counterpart and the embodiment of steam. He most often appears in compact masculine but at the same time defensive and broad lines. This is yet another way to express that one has already dismissed this energy system as one of the past and has become aware of its high social and ecological price.

A price that is once more appraised in literature: among the later works of Émile Zola (1840-1920), one of France’s greatest realists of the 19th century, is a novel with the sober prosaic title Work (‘Travail’). The story is set against the ominous setting of a steel mill named abyme, which translates into ‘abyss’, or even more drastically into ‘Hölle’ (hell) in the German version of Leopold Rosenzweig. This evokes the heat and hiss of the furnaces and steam plants on one hand, and on the other hand, the wretched living conditions of those who work there and must fight for their daily survival. According to one of Zola’s central theses, work is corrupted in such conditions, does not benefit the community or have any democratic aspects, nor does it help those who carry it out achieve a free existence. If you will, Zola deals with a paradox: work is no longer the basis of culture, but leads to its destruction. What is striking in this context is the constant aggression and the omnipresent alcoholism, which are direct consequences of the working conditions. About steelworker Fauchard, he writes the following: “His ration meant four quarts of wine a working-day, or night, and he said that that was but just enough to limber up his body, so completely did the furnace dry up all the blood and water that was in him”.

The tale takes a lighter and distinctly utopian turn, however, when the hero Lucas Fremont, an engineer, enters the scene. Through his clever use of electricity, he transforms the city of workers into a modern and liveable place. One must remember that the picture painted here is neatly black and white. In any case, though, it is historically significant that a new character is gaining in cultural in literary prominence: the engineer, who embodies progress and carries out an absolutely heroic social task. In Zola’s work, this Lucas Fremont appears as a young man of twenty-five but leaves the story after some six hundred pages in his old age, looking back on a successful life’s work. He set in motion an energy transition, with which the meaning of work also took a turn, since it could unfold its collective potentials.

Literature

- Marcel Proust, Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Zeit, übers. v. Eva Rechel-Mertens, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 2000.

- Émile Zola, Arbeit, übers. v. Leopold Rosenzweig, Verlag Th. Knaur, Berlin 1928.

Research recommendations

- Ulrike Sprenger, Proust-ABC, Reclam Verlag, Leipzig 1997.

- Imke Buck, Der späte Zola als politischer Schriftsteller seiner Zeit, Mateo-Monographien Bd. 27, Mannheim 2003. www2.uni-mannheim.de/mateo/verlag/diss/buck/buck.pdf

- Klaus Plitzner, Elektrizität in der Geistesgeschichte, Verlag für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaft und Technik, Bassum 1998. Darin insbesondere: Ulrike Felber, „La fée électricité. Visionen einer Technik“, S. 105-121.

- Rolf Spilker (Hg.), Unbedingt modern sein. Elektrizität und Zeitgeist um 1900, Rasch Verlag, Osnabrück 2001. Darin insbesondere: Jürgen Steen, „Die fée électricité trifft Prometheus – Die internationale Elektrotechnische Ausstellung 1891 und die ‚Neue Zeit‘“, S. 34-49.

Towers and thunderbolts

The story is a little chaotic and, yes, even somewhat exaggerated, but it is a joy to read: in present-day Paris, two secret agents plan to destabilise the North-Korean dictatorship, but they do not have the dirty agent trade in mind. The two think they are very clever and plan to tear down the hierarchy using the soft but anarchistic energies of entertainment and musical amusement. The secret weapon being deployed is a famous French pop hit, or more precisely, its interpreter, who has scores of fans in North Korea. The West uses the weapon of entertainment to cause distraction.

This story, which could easily be imagined as a Monty Python film, not least because of its satirical tone, was penned down by the French author Jean Echenoz (1947*). In 2016 he published his novel Special Envoy. The title refers to this singer, Constance, the ‘perseverant’, who is mainly selected for her undaunted character. Part of her rather in- or semi-voluntary retraining from singer to agent is a long stay in one of France’s southern Departments, including in the following, very particular place:

The next morning, Constance enjoyed a wide panoramic view of over 180° thanks to the all-round glazing [...]. At regular intervals, the view on this landscape was briefly interrupted by some kind of pin or paddle rushing by, until she understood that it was a blade of an enormous propeller and that she was therefore occupying the nacelle of a wind turbine, all the way at the top of such a device, as one sometimes sees from the car, off in the far-away distance. Who would have thought that the latest models could also, in addition to their function of converting wind into energy, act as an accommodation, even if after a very rudimentary fashion.[1]

It is worth mentioning that this scene on the tower and in the wind turbine’s nacelle has hardly any significance in the story. The exact opposite is the case, the plot takes a break here and runs a short extra lap, as it were. The view from the tower is therefore dramatic idleness, a poetic surplus. Exactly because of this, it marks a highlight in the text and occupies a special place which might remain longer in the reader’s thoughts than the rest of the secret service plot. Perhaps Jean Echenoz was travelling by car through the sparse fields of the southern Departments and thought that the current energy architecture should at least once be connected to the long symbolic history and iconography of tower construction. Maybe this could be used to play around a little in a literary way and remind us of the houses of the hermits, ivory towers or the Rapunzel motif... Whatever the case, the passage not least demonstrates in all its playfulness that architecture, and especially tower architecture, resonates with the power of imagination and artistic imagery. Meanwhile, Jean Echenoz’s interest in energy is more pronounced, certainly elsewhere in his work. Let’s continue and move away from the tower.

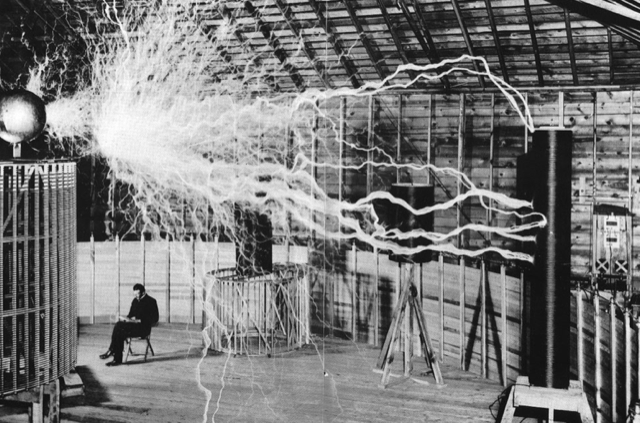

In 2006, in a novel titled Lightning, Echenoz follows the biography of a Croatian emigrant and as such dives deep into the energy history of the 19th and early 20th century, which would be strongly impacted by the arrival of this migrant in the USA. Gregor is the name of his hero, who grows up as the child of a pastor in a small town in the Croatian mountains. He proves to be a highly gifted pupil, who is particularly at home in the world of numbers and technology. His later engineering studies in Graz and Prague, however, are far from uneventful. Perhaps it is already clear at this time, that the torrent of ideas which he undoubtedly produces and only finds applications for in his first own inventions, is mirrored by a constant unconventionality. A number of quaint character traits also emerge, which apparently amuse Jean Echenoz and are once again given the Monty Python treatment. This is illustrated by a number of painfully curious fears of germs, bacilli, jewellery and especially pearls. At the same time, a strong attraction to birds, especially pigeons, arises, as does a pronounced penchant for a luxurious lifestyle and an expensive wardrobe: scarves, hats and finger gloves that are constantly changed for the sake of cleanliness. And then there are his arrogant desire to go it alone, paired with his tremendous naivety with regard to the legal and economic interests of his projects. The latter will lead to it that he is often negligent in patenting his later inventions, contributing to the rapid financial ups and downs of his biography.

Gregor’s path leads him to Paris, then New York. In addition to many other inventions (such as neon tubes or radio), he develops the alternating current system used to electrify the USA. Echenoz: “It is clear that this concerns a very extensive project. A considerable operation. A plan without equal.”[1] And naturally, one has long understood that it is Nicola Tesla (1856-1943) to whom Jean Echenoz has dedicated a biographical novel. What is important here, as is typical of the genre, are not necessarily the biographic details, which are given a very free and fictitious treatment. Rather, the novel seems to be more concerned with capturing the innovative events that unfolded around 1900 and during the first decades of the 20th century, with their immense momentum and creative chaos. And it succeeds in its intent. The main focus is the so-called war of the currents that was waged between former technology magnate George Westinghouse (1846-1914) and another exceptional inventor of his time, Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931). This war of currents was sparked by the question which type of current should be used to supply the North-American continent. Edison favoured direct current, which could nevertheless not be transmitted across large distances. Westinghouse, however, put his faith in Tesla’s alternating current technology, exactly that energy that could ultimately be developed further so that it still supplies us with power today and has conquered almost the entire globe.

In the years of the war of the currents, Tesla’s genius is not least exhibited by combining the disciplines of engineering and entertainment. He travels the country and demonstrates the power of electricity on the scene. Tesla knows how to present himself on stage; his strikingly tall figure of almost two metres and his equally elegant and photogenic appearance do the rest. He is the Master of Lightning. These spectacles are still intertwined with the energies of the romantically mysterious electricity, however, with the difference that Tesla also presents himself in his capacity of engineer, in other words, as the person who has seen through this power, controls it and can build devices to reliably use them. In the long run, however, the enormous potential he and the electrification unfolded, would not profit him, while others, especially Westinghouse, would capitalise on it. A victim of his economic naivety, Nikola Tesla sinks into poverty in his old age and retreats entirely from the public and scientific life.

TESLA. These two elegant-sounding syllables would rise to fame once more a turn of a century later, and once again surround a story of sweeping innovation. It emerged from the realisation that our mobility must be organised largely without the combustion of fossil fuels and the emission of CO2. To describe the basic extent of this project, one might be tempted to quote Echenoz again and apply his phrases with some élan to the history of energy systems: “It is clear that this concerns a very extensive project. A considerable operation. A plan without equal.”

Two engineers from the USA, Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpening, were inspired in 2003 to christen their electric car the ‘Tesla'. It should meet certain requirements: it would have to be elegant and sporty, a roadster, which on the one hand would be good for the weight and range, and on the other hand appeal to a segment for whom a car with a large combustion engine is no longer just an ecological problem, but also more and more a question of aesthetics. Elon Musk will later finance the start-up and become its CEO. After the luxurious models developed at the start, the company entered the broader segment with its Tesla 3; by late 2018, its production had increased to one thousand cars a day. In the meantime, the brand name has become one of the most powerful driving forces of the traffic transition and e-mobility. And let’s not forget the entertainment value: in 2018, Elon Musk shot his own red Tesla into space using rocket technology that was also developed by him. The name also seems to be attached to highly energetic extravaganza.

Whatever the case may be, the name Tesla stood and stands for inspirational momentum and for a peculiar sense for the future. A sense that sees the opportunities of novelties and provides a flood of images, narratives and justifications that oppose the outmoded ideas of the powers that be. Nikola Tesla’s alternating current technology was initially seen as a fad. Even the idea that electricity could become the predominant form of energy was long considered preposterous at the previous turn of the century. Around the year 2000, circumstances were similar: electric mobility was often objected to as being no more than an eccentricity. The notion that the vehicles could be mainly driven by renewable energy, was equally dismissed.

The name Tesla manifests itself in these events through sheer tenacity and as a symbol of things to come. Echenoz’s portrait of Nikola Tesla shines a spotlight on the dynamics of innovation at selected moments of the history of energy. Not least, however, Echenoz also imparts on his readers a feeling for Tesla’s or ‘Gregor’s’ weaknesses and his tragic fate. It must have been his solitude: a figure like a lone tower, with too few friends, too few comrades-in-arms.

[1] Free translation

Literature:

- Jean Echenoz, Unsere Frau in Pjöngjang, übers. v. Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel, Hanser Verlag, Berlin 2017.

- Jean Echenoz, Blitze, übers. v. Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel, Berlin Verlag 2013.

- Nikola Tesla, Meine Erfindungen. Eine Autobiographie, übers. v. Daniel Fedeli, Sternthaler Verlag, Basel 1996.

Research works:

- W. Bernard Carlson, Tesla. Der Erfinder des technischen Zeitalters, übers. v. Elisabeth u. Thomas Gilbert, FBV, München 2017.

- Frank O. Hrachowi, Tesla. Die Geschichte einer Automarke, Edition Technikgeschichte, 2017.

- Dororthea Schmidt-Supprian, Spielräume inauthentischen Erzählens im postmodernen französischen Roman. Untersuchungen zum Werk von Jean Echenoz, Patrick Deville und Daniel Pennac, Tectum Verlag, Marburg 2003.

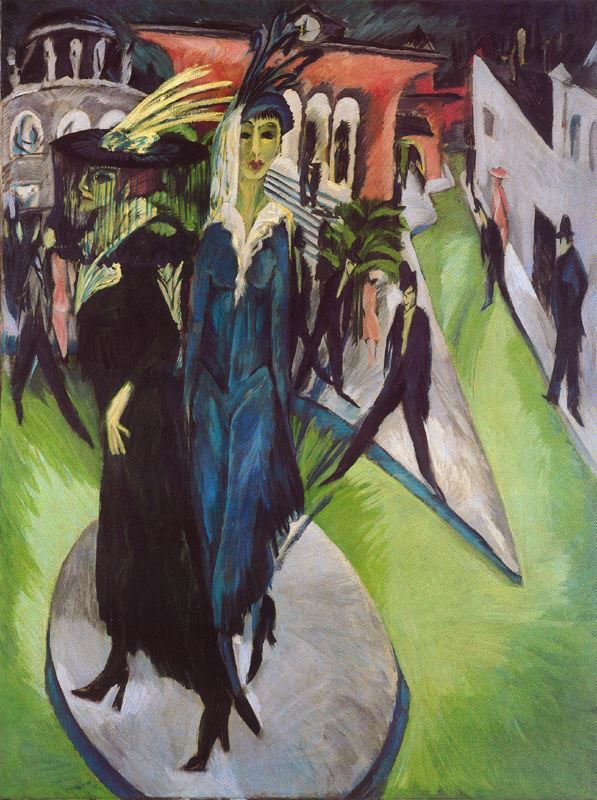

Metropolis

Expressionism. This word immediately brings images to mind: like the bright metallic film scenes of Metropolis (1927) by Fritz Lang (1890-1976), the energetic and frank colours of paintings by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) or Franz Marc (1880-1916), the jagged, almost lightning-like letters on the film posters and book covers.

Literature also leads to bizarre surroundings, like in the world of Franz Kafka (1883-1924). What readers find here emanates a strangely familiar confusion, which we describe today with the frequently used "Kafkaesque". My spelling program no longer underlines this little word; the literary sphere has long since handed over the expression to the broader vocabulary and at the same time named a feeling that helps to describe modern living environments to this day.

Even though dating art epochs is always a rough process, Expressionism takes up about the first three decades of the last century. The most catastrophic event in the middle of this period is therefore World War I. This event is even more monstrous because of its completely new technical and energetic dimensions. The war was an incomprehensible and destructive explosion of energy that was unleashed in the hearts of the highly industrialised European culture in 1914. It is becoming more and more urgent to ask whether technology and energy are destructive or even monstrous forces. The answer to this question is yes: a technological world that has become fatally independent and uncontrollable is always a centre of gravity for the arts and literature. Expressionism also shows this in its descriptions of cities or modern worlds of working. The industrialised metropolis appears as a dazzling place charged with energy and full of roaring noise. Especially the expressionist metropolitan lyricism repeatedly immerses itself in this “machine war”, for instance in Georg Heym’s (1887-1912) poem Ophelia of 1910. Electrified cities pervaded by energy infrastructure come to life here with a demonic and monstrous appearance.

A fantastic potential already surrounded electricity in the dramas of the Romantic period, when the idea arises to create artificial life using energy. Automatons are created that threaten to escape their creator’s control with fatal consequences. The most famous example is undoubtedly Mary Shelley’s (1797-1851) Frankenstein of 1818. From Shelley's horror figure, the lines lead into the pictorial worlds of the expressionist arts and into a world of technology that confronts man as an uncontrollable being. We observe a coalescence of physics and fantasy, a boom in fictional tales.

Like hardly any other epoch, Expressionism is able to see how the physical phenomenon of energy is reflected in cultural forms of expression: in texts, images, designs and films. Dance and theatre also visualise and make it possible to experience energies. Energy is not just a partial aspect of this culture, but, as one is tempted to phrase it, culture appears as an energetic phenomenon.

Gasand Gas II are two plays by Georg Kaiser (1878-1945), one of the most popular playwrights of this age. The plays appeared in 1918 and 1920. Especially the first part was enormously successful on the German scenes and is considered one of the sources of inspiration for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. What’s more, the play is by no means light fare, the plot is an obscure staccato and the characters are not given names. Kaiser prefers to use anonymous job descriptions such as engineer, worker, writer, government representative or billionaire’s son. These 'names' - including the latter - are less about describing individualities than the constraints of relationships. The setting remains abstract and can only be identified as a factory hall or a factory site. Even the gas that gives the title to the piece is not specified and does not even have an approximate chemical definition. There are nevertheless two things that become clear: on the one hand, that it concerns the development and production of a fuel type that will be far “mightier” than the competing forms of energy:

coal and hydraulic energy are outdone. The new form of energy moves millions of new machines with more powerful propulsion. We create it. Our gas feeds the technology of the world.

On the other hand, that this technological potential remains uncontrollable, so that a surprisingly precise allegory with regard to the massive side effects of atomic and fossil energy production emerges in Kaiser’s energy drama. That is also why the play starts with the report of a serous accident: an explosion that destroys the factory and claims innumerable victims, despite the fact that no one committed any error. Even the technical engineer responsible can claim in all honesty that he was always right. However, he has to note the character of his calculation, his "formula", as having fallen into a dilemma that is as technical as it is philosophical:

Right - and not right! We have reached the limit. Right - and not right! There is no example for this. Right - and not right! It calculates itself and turns itself against us. Right - and not right.

Thus the relationship between energy and society in the last year of the First World War appears to have become acutely paradoxical and metaphysical.

Taking a few steps back from this combustible substance, one notices that more detailed trains of thought lead to the cultural history of the early 20th century. This for example concerns the prominent role of the engineer in the play. The profession of engineer is gaining new visibility and acknowledgement in this era, not least in connection with new academic regulations, as around the turn of the century, the academic degree of engineer and their right to earn a doctorate was introduced in the German Empire. At the same time, some members of the profession recognised that their field of activity should not only include technological developments, but should also consist of social reflection and communication about technology. The insight behind this seems to be that technological innovation and transformation phases are very complex processes that can be better understood and shaped if one also looks at their cultural facets. What engineers do therefore also has a cultural side in addition to the technological (and the obligatory economical and legal) aspects. This requires a look beyond the horizon and a joint development of disciplines. An exemplary figure for this foresight leads us deeper into the domain of electricity: Munich-based engineer Oskar von Miller (1855-1934). Miller had a highly successful engineering company that realised important power plant and electrification projects such as the then largest water storage power plant in the world on the shore of Bavaria’s Walchensee. (This plant, a protected monument since 1983, still generates renewable electricity in the more atomic-fossil energy mix of the Uniper group.) Not only that, but Miller was also active as a museum founder and director. And with plenty of panache. He first gained experience at the major electricity exhibitions of the late 19th century in Paris in 1881, in Munich in 1882 and in Frankfurt in 1891. While the technology was presented here in event format - the main attractions were mostly the still experimental long-distance transmission of alternating current - Miller thought of giving the interested public a constant insight into technological developments. In May 1903, he first publicly voiced the idea of building a technological and scientific museum in Munich. He was inspired by already existing houses in Paris and London he had visited. The rest reads like a magnificent success story: after the first exhibitions were soon shown in temporary premises, the impressive Deutsche Museum on Munich's Museum Island was founded in 1925. Miller proved to have a great talent for organisation with equally original and paternalistic traits. For example, in the sources and the research literature, there frequently appears a bizarre sentence with which he identified the Deutsches Museum as his sovereign domain: “Here, anyone can do what I want.”

Miller’s concept consisted in designing the museum as a living educational format. It was conceived as a site that could be visited to learn about the history and development of technology, bring it closer to the visitors’ attention and ideally inspire them. This scholarly focus was necessary, as Miller put it, because “industry and the technical sciences [...] are coming into their own in all cultural domains.”

If you look closely, two points of innovation are named here, one of which, obviously, is technology and science. The other is the result of any historic look beyond the horizon, with which engineer Oskar von Miller taps into the cultural sphere. In it, the museum plays a central part as a downright medium to inform the general public. Miller’s project is furthermore one of a wide range of innovative museum concepts proposed during this period, which in part can also be described as a museum reform. What appeared here in the exhibition landscape - be it technical and scientific artefacts, arts and crafts, or the works of the expressionist avant-garde - was intended to have an effect on the everyday lives of its visitors. One of the central ideas of this very progressive, open and undogmatic culture could readily inspire our present day: the success of modern life projects and the opportunities of a future-oriented community are not least based on the coalescence of technological and aesthetic resources.

Literature

- Georg Heym, Werke, Reclam Verlag, Stuttgart 2006.

- Georg Kaiser, Gas / Gas. Zweiter Teil, Reclam Verlag, Stuttgart 2013.

- Mary W. Shelley, Frankenstein – oder Der neue Prometheus, Verlag Das neue Berlin, Berlin 1978.

Research recommendations

- Thomas Anz, Literatur des Expressionismus, Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart 2002.

- Žmegač, Viktor: „Zur Poetik des expressionistischen Dramas“ in: Reinhold Grimm (Hg.), Deutsche Dramentheorien II: Beiträge zu einer historischen Poetik des Dramas in Deutschland, Athenäum Verlag, Wiesbaden 1981, S. 154-180.

- Wilhelm Füßl, Oskar von Miller 1855-1934. Eine Biographie, Verlag C.H.Beck, München 2005.

- Anke te Heesen, Theorien des Museums zur Einführung, Junius Verlag, Hamburg 2012

Atomium

One can hardly still call it painting: around 1946, Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) started working the canvas by placing it on the floor of his workshop instead of in the traditional vertical position, for instance on the easel. Instead of painting, he used gravity to create images. Entirely new forces were unleashed: chaotic streaks, rhythmic series of lines, small and uncountable colour flows, and drops, many drops. This process is called dripping or action painting: the painter stands with his legs apart or bent artistically over the picture in the making, paint container in one hand, brush, misappropriated as a spraying tool, in the other hand. Sometimes he also drills a hole into the bottom of the paint can, from which the paint flows. A seemingly angry handling, gestural, spontaneous, fast. Deliberately, he creates chaos on a large format. Thus a new, forceful break is made with the long-standing, especially European tradition of figurative art. This departure from a current form is called informal or even abstract expressionism, an avant-garde movement which also included such fellow colleagues as Willem de Kooning (1904-97), Joan Mitchell (1925-92) or, in Germany, Karlo Otto Götz (1914-2017).

In the late 1940s, Pollock’s drippings, often numbered rather than titled, quickly rose to fame. With the outrageous energy of this art form, he struck a nerve in his day. Pollock himself describes this neuralgic and not least traumatic point. He only used a few words to articulate how artistic forms of expression, such as media, infrastructure and energy scenarios intersect. In an interview taken in the summer of 1950, the then 83-year-old painter stipulates:

It seems to me that the modern painter cannot express his age, the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio, in the old forms of the Renaissance or any other past culture. Each age finds its own technique.

The remarkable thing about this quotation is first of all that Pollock does not explain his art from the perspective of art history, he does not sketch any historical course or evolution in painting. For example, it is not about traditions or the influences that significant predecessors have exerted. What Pollock does is rather to outline the cultural web that forms his age. The explanation is therefore not given by time, in diachronic form, but rather by neighbourhoods, i.e. synchronous, simultaneous connections. Orientation takes place beyond the horizon; it is transdisciplinary and inspires us to inquire into parallels between cultural phenomena. (As a reminder: a similar interpretation was already used by Michel Serres, which made it possible to relate William Turner's painting to physics and Sadi Carnots' thermodynamic paradigm. See e-story no. 2.)

Let's just stick to the arts for now: the explosive energies made visible by Pollock's pictures can also be found in the music of the 60s. It is thanks to the Internet that, for example, the last live sounds of the jazz saxophonist John Coltrane (1926-67) can still be heard and the events on stage can also be seen in a few short camera recordings. At the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1966, almost nothing remains of swing jazz. On a radiant summer day, John Coltrane, his wife Alice on piano, co-saxophonist Pharo A Sanders, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Rashied Ali start improvising. Like the painter Jackson Pollock, they perform on the edge of chaos and produce extremely free sounds and rhythms with their instruments. Author Kat Kaufmann (1981*) writes aptly about these evolutions in jazz:

Since the sixties at the latest, jazz has been demanding, eruptive, searching, wild - a music that expects you to let go of prefabricated expectations, for example, likeable, pleasing clichés and performance styles adapted to mainstream taste such as "You like tomato and I like tomato" by Louis Armstrong.

One of their last concert tours took the quintet to Japan, one of the gravitational centres of avant-garde jazz at the time. It's hard to imagine today that an art as extraordinarily challenging and exhausting as Coltrane's would produce scenes more familiar in popular fan culture. At Tokyo Airport, the free jazz formation was welcomed by hundreds of enthusiastic people. Most surprised of all was probably John Coltrane himself, who is said to have inquired from a fellow traveller whether there was a high-ranking state official on board who was subject to this reception. The good fourteen days that the quintet spends in Japan are packed with concert dates, and not just limited to the big cities. Modernity in all places. Many of the concert locations are covered by the Shinkansen express train, which was only put into operation in 1964 and symbolises the fast and high-tech Japan.

At the same time, the visit of the musicians revolves around the events of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, which took place just over two decades ago. Coltrane saw himself as a political artist who had already taken a musical stand in the anti-racism protests with songs like Alabama. Peace on Earth is the title of a twenty-minute piece that revolves around the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and was written exclusively for the Japan tour.

Literature and film are also at the point to dramatically change their means of expression. This evolution is also closely related to the first traumatic experiences with the new form of energy. In the late fifties, the young director Alain Resnais (1922-2014) pursues a documentary project about the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima. However, he soon changes his plans and decides to turn a feature film on the subject instead. He asks script writer Marguerite Duras (1914-1996) to write the scenario. In 1959, the film Hiroshima, mon amour premiers and becomes one of the strongest impulses of a cinematic revolution called the Nouvelle Vague. Among this new wave are the most famous directors of 1960s’ France and an equally imaginative and comprehensive unleashing of the artistic potential of cinema. At the same time, the trend is an open revolt against commercial storytelling as a far too linearly, aesthetically and psychologically simple format. Away from cinematic conventions and clichés, there is a great deal of experimentation with the artistic independence of film: these include editing techniques, camera work, the handling of soundtracks or film music and, above all, directing. It is not for nothing that one speaks of directorial cinema when it comes to describing a self-confident and free handling of the film medium.

From this perspective it is to be excused that the attempt to reproduce the plot of Hiroshima, mon amour is somewhat embarrassing. The 90-minute film grants the opportunity to follow two characters. They do not have names. She’s French, he’s Japanese: an architect and an actress. A random encounter, a budding love affair during shared walks and in hotel rooms in Hiroshima. Images of the earlier destruction of the city and of a rebuilt and repopulated Hiroshima alternate with intimate scenes.

While viewing, one becomes remarkably close to the two figures, follows the 'I' and 'you' of their dialogue and receives lasting impressions, but nevertheless they remain but the woman from France and the man from Japan. It is a story that is told emphatically yet remains very abstract at the same time. It unfolds in a very free pictorial context, characterised on the one hand by angular montages and jump cuts, and on the other by pauses and stretched shots. The story also displays another temporal and spacial facet by delving deeper into the past of the Second World War. Thus the woman takes centre stage, her youth in the French town of Nevers on the Loire, her social ostracism, which goes back to a love affair with a German soldier, what was called ‘horizontal collaboration’. It is quite obvious in all this how much global historical events and the most private sides of existence permeate each other. It is exactly this aspect that seems to be require new forms of expression and storytelling here in Hiroshima, mon amour. The film also shows that a large number of aesthetic conventions and narrative strategies no longer suffices and has to be reformulated under the conditions of a modern age that not least includes the experience of atomic energy and destruction.

The view of the arts and the artistic avant-gardes of the first post-war decades is - as the three examples show - a view of the beginning nuclear age. The fact that these artistic testimonies are by no means easily comprehensible or palpable, points not least to the fact that the atomic scenario has crossed the boundaries of portrayal and perception. Still, art remains like a key, an irreplaceable key that can open cultural or historical realms and make their inventories, events and life more understandable. Art accomplishes something very specific: it captures its time or present into thoughts, feelings and shapes.

Atomium. 1958, World Expo in Brussels. This Expo was an attempt to bestow a different, positive shape, a new narrative on atomic energy. This plan had its predecessors, particularly in the USA, which attempted to escape the shadow of the events of August 1945 under the auspices President Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969). Eisenhower launched the campaign Atoms for Peace and initiated the foundation of the International Atomic Energy Organisation (IAEO). Thus the narrative of the peaceful and socially widespread use of nuclear energy also takes shape. Its most impressive architectonic reflection is found in 1958, at the very heart of Europe: the Atomium, a 102 metre high iron cristal, magnified 165 billion times.

Iron atoms as a model? Yes, the link to the radiant and fissile substances is not strictly drawn in Brussels, as the aim was to present the broad field of scientific and engineering innovations and also heavy industrial iron processing in atomic models and thus to "think nuclearly". Scientific historian Jochen Hennig notes that the Atomium "became the emblem of an apparently all-encompassing atomic age".

Thus it fulfilled its landmark function and in practice was a place for exhibitions, events and gastronomy; a bright, enlightened and spectacular place to help integrate the atomic age into the progress pattern of the industrial age: once again, a new, practicable and more powerful energy is emerging with the promise to solve the central supply problems of modern societies. On the one hand, however, nuclear technology had already become a mortgage that could no longer be settled; on the other hand, it became increasingly clear that progress towards controlling the world and nature is not a simple and linear process, but is double-edged and surrounded by complex side effects. The technical potentials may grow rapidly, but each generation must try to ensure responsible handling of them anew by correcting its technologies, concepts and mindsets.

In the early 2000s, the demolition of the Atomium, which was now in great need of repair, was up for discussion, but in a specially held referendum, eighty percent of Brussels’ citizens were in favour of preserving and restoring the building. The former ideas and visionary promises of nuclear technology no longer played a significant role. The new century adopted the Atomium as an architectural marvel, an aesthetically pleasing monument. The ironic conclusion is that while technology changed, art remained young. Apparently because it succeeds more reliably in maintaining a link with the future, in making it tangible, perceptible and, in this case, accessible.

Literature, sources and texts for research

- John Coltrane footage at Newport 1966: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=as1rTILOZDQ

- Marguerite Duras, Hiroshima mon amour, in: SPECTACULUM. Texte moderner Filme. Bergman – Duras – Fellini – Ophüls – Visconti – Welles, Suhrkamp Verlag, hg. v. Enno Patalas, Frankfurt a. M. 1961.

- Jackson Pollock im Interview mit William Wright, in: Erika Doss, Benton, Pollock and the Politics of Modernism. From Regionalism to Abstract Expressionism, University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1991.

- Alain Resnais, Hiroshima, mon amour, 1959.

- Jochen Hennig, „Das Atomium. Das Symbol des Atomzeitalters“, in: Gerhard Paul (Hrsg.): Das Jahrhundert der Bilder 1949 bis heute, Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, S. 210–217.

- Kat Kaufmann, „Wo spirituelle Visionäre ihren freien Fall vollziehen, gelten irdische Gesetze nicht“, in Süddeutsche Zeitung, 14. September 2018: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/emanon-von-wayne-shorter-wo-spirituelle-visionaere-ihren-freien-fall-vollziehen-gelten-irdische-gesetze-nicht-1.4128199

- Lewis Porter (Hg.), The John Coltrane Reference, Verlag Taylor and Francis, New York 2008.

Oil / Sun

The author of this essay was born in 1976. Grown up in the southernmost part of the former DDR, in the Obere Vogtland, he now feels that a lucky circumstance of this childhood was that he lived in an area of the socialist country where good reception of western public television was possible. One of the things I remember fondly are the regularly broadcast children’s and early evening programmes and the fun I had watching them. Another fond memory are those broadcasts that I could only watch if I had “overstretched” my bedtime or could stay up late. I then watched what my parents liked, and their interests have stayed with me.

Obviously, this mainly concerns the recurring formats, which were highlighted enough to make it into my long-term memory. Firstly, this includes those that the critical journalism and therefore part of the core inventory of democratic culture brought to the living room of the East. Iconic formats, partially with energetic theme songs and titles, which today still convey the determination of research journalism: Report, Monitor, Contrast, Panorama. A self-aware and critical ratio was propagating. It was a sibling of the progressive movements and thinkers that a few years later, in the nearby Plauen (in today’s Saxony), impressively succeeded in instigating a peaceful revolution and therefore free historical potentials for democracy and reform.

Secondly, in addition to the informative apparatus of the political magazines and investigative journalism, there was a machinery of fiction that ran with the same weekly cycle. This machinery, which brings us to the topic at hand, was oil-driven. There were two main periodicals: the television series Dallas and Dynasty. Because my young eyes kept falling shut and the subject matter of both prime-time soaps was pretty boring and slow-paced, the storylines intermingled and Dallas-Dynasty became a singular entity. Only a handful of names remained, which I could not with absolute certainty link to one series or the other: JR and Bobby Ewing, Sue Ellen, Alexis, Blake Carrington, Dex or Dexter, Fallon, Krystle, Miss Ellie, Cliff Barnes, Pam, Sammy Jo, April, Dusty Farlow, the Colbys.

These proper names and characters are the particles of an oil film, even though it actually concerned two oil dynasties, whose wealth and fortune were fed by oil, whose intrigues and adventures began and ended in the oil business. Dallas first aired in 1978 and was broadcast by the CBS network. In 1981, the ABC network stoked the fire with its own Dynasty. The pilot for Dynasty, which aired in 1981, had nothing but the raw material for its title and was therefore simply called: Oil. The fact that the prime-time soaps spun this huge visual web around the fossil raw material in a weekly cycle over many years fits seamlessly into the cultural-historical findings: one cannot help but strike oil at the basis of America’s twentieth century and the source of the generated wealth. The myth of the American Way of Life, a combination of adventure, heroism and clichés, with its wealth and opportunity, was a piece of oil poetry in the twentieth century; a narrative that inevitably led through prospering oil fields. In 1966, Merril Wilber Haas (1910-2001), then President of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, stated without the faintest doubt interfering with his self-conscious insight:

[Our] ‘American Way of Life’, the envy of most nations in the world is based largely on the energy and the products of the petroleum industry which are derived from our success. It is almost impossible to separate the good things of our life, which often make life worth living, from the petroleum industry.

Looking back, both soap operas appear to be remarkably successful narrative developments: the mass medium of television that brought the dynasties of the Ewings and Carringtons to life, also provided the energy sector with images, smart design and made it part of the cultural canon. Furthermore, the narrative’s global, border-crossing characters and the wages of those days are astounding. Both television series that dominated the eighties are two outrageously solid storylines about natural oil, which pervaded Western culture from the USA.

Against this background, it is easily explained that the reflection on the watching habits of my childhood described above so single-mindedly focuses on these stories. It was not least oil that illustrated and opened up the global and adolescent world to me in the 1980s in an East-German living room in the Vogtland. My first cultural lessons were for a large part learned in the circles of the Carringtons and Ewings.

Of course, I wondered whether, and if so, how this connection of raw material motives and socialisation continued. If I move a bit further along the autobiographic timeline, the road would probably lead eastward from Dallas and Denver, where I found a new focus for my imagination in sunny Florida. The road leads to the flashy and fascinating aesthetics of director Michael Mann’s (*1943) Miami Vice. At first sight, the crime series is not an oil story, ultimately most of the stories revolve around cocaine. Still, the imagery of Miami Vice is nothing if not a pure burst of energy. This is already apparent when one allows the fifty-six-second acceleration to take effect, with which the famous opening credits bring the individual episodes up to speed. A dynamic of the themes: low-flying shots of the sea surface, horse and dog races, agitated flamingos, women's bodies in rapid motion, motorboat races and the jai alai or pelota game, the fastest of all ball games. Having been brought up to speed, the visitor later discovers another icon that is at the heart of the series, next to investigator duo Sonny Crockett and Ricardo Tubbs: a white Ferrari Testarossa, which reflects the electric lights of nighttime Miami onto the asphalt in soft pastels. Images full of energy and tempo, arranged to the sound of a combustion engine. These twelve cylinders are perhaps injected with the oil from Texas or Colorado, from Dallas or Denver, to be mixed with the aesthetics of goods, the imagination, life plans and fashions on an enormous and, as of 1989, even limitless scale. Whoever reached adulthood in the 90s, became part of the manifold cultural manifestation of natural oil without even noticing, and certainly without questioning.

Bill McKibben, one of today’s most prominent US climate activists and author of books on climate change, speaks of Northern America as an 'oil-soaked continent’, a metaphor to describe the oil-drenched social-cultural sphere. His writings can easily be generalised with regard to the late fossil Western culture: ‘That oil has gotten into our brains and done much to make us who we are – it’s very useful to recognize that, so we can maybe do something about getting beyond it.’

Which realisation does this look on the history of television series and the approach to the subject of oil provide? First of all, it gives us insight into the media history of energy narratives. Dallas and Dynasty teach us that these stories received a mass-media and expansive format: week after week, raw material stories were broadcast across the television channels. In contrast, literature, as well as other artistic genres, appear as rather marginal media with little reach and power. This can be contrasted with an early observation by Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956), which calls into question the literary, and especially dramatic, depiction of the petroleum complex. In On Materials and Forms (Über Stoffe und Formen, 1929), he already stated that the mental capacity and the presentation logic, based on clear distinctions, of classic forms of drama no longer suffice: petroleum, according to Brecht, “balks against the five acts”.

Of course, oil also plays a role in the American literature of the 20th century. Worth mentioning are Upton Sinclairs novel Oil!of 1927 and Edna Ferbers novel Giant from 1952. Nevertheless, these stories mainly garnered attention outside the world of literature as Hollywood productions. While Oil! was the template for There Will Be Blood (2007), in which both lead actors, Daniel Day-Lewis (*1957) and Paul Dano (*1984) captivate us with their portrayal of the physical and mental hardships of the early oil business, Edna Ferbers story found its way from the page to the silver screen much earlier. In 1957, George Stevens (1904-1975) adapted the story with Elizabeth Taylor (1932-2011), Rock Hudson (1925-1985) and James Dean (1931-1955). Here, the wasteland of the Texan desert became a region of transformation, where traditional cowboys first raised livestock before immense wealth was generated from oil. Cultural theorist Melanie LeMenager already sees the rise of a “genre of pro-oil propaganda” in the film adaptation of Giant. According to her, Dallas is another, later contribution to this propaganda.

The second insight concerns our present day; it is best demonstrated in the form of a thought experiment, an attempt to create a sort of blueprint: I imagine a similarly powerfully produced narrative, a fiction series that is as coherent as Dallas or Dynasty, based on the theme of renewable energy. The wide panorama, a sort of remake or adaptation, are conceivable: a company saga in the segment of major renewable power stations, an offshore wind farm or a solar power station. The title of the pilot could be as pointed and simple as the one for Dynasty, just three letters: Sun.

I am already laughing inside. I assume that it would quickly become apparent that many of the staples of the oil narrative no longer fit and would have to be dropped. They no longer “work” and cannot simply be transported to the modern age. Things would soon become funny: as much as the heroic characters and myths in the style of the American Way of Life are stereotypes, as used-up is the narrative coupling of the dynastic family model and the liberal-expansive way of life and business, as pretentious perhaps the entire concept, iconography and design. The thought experiment is a failure and no blueprint can be established that matches both energy eras.

By the way, the garish, almost grotesque aspects displayed in the two first seasons of the 2017 Netflix reboot of Dynasty confirm this suspicion. Carrington daughter Fallon even breaks the oil family’s business tradition by heavily investing in wind power. Still, this only happens in the margin of a jumble of storylines that mainly serves the excessive product placement of luxury goods and ends with the realisation that the consumption of oil amounts to a never-ending party. Decoration and extravaganza push the development of character and energy evolutions to the background. Perhaps the only interest of the series lies in its attempt to make the American billionaire into a new type of hero. It is reassuring that this is a failed attempt: the only thing that is highlighted are the usual clichés and ultimately a foundering, late fossil phantasmagoria.

Must narration and its arsenals, like forms of energy, first undergo a kind of modernisation? (This is a question that requires further consideration.) The fact that this has not happened yet and that a narrative project like Sun does not exist, however, also shows how small the share of renewable energies in our imagination and fiction still is compared to oil (or, as stated in another essay, compared to coal).

We are even crossing a narrative no man’s land, in which Oil can no longer be told and Sun cannot, as it seems, be told yet.

Literature, sources and texts for research

- Dallas, television series, CBS 1978ff.

- Dynasty, television series, ABC 1981ff.

- Miami Vice, television series, NBC 1984ff.

- Upton Sinclair, Oil! A novel, Albert & Charles Boni, New York 1927.

- Edna Ferber, Giant, Doubleday, New York 1952.

- Paul Thomas Anderson, There Will Be Blood, 2007.

- Robert Stevens, Giant, 1957.

- Bertolt Brecht, “Über Stoffe und Formen”, in: Brecht, Große kommentierte Berliner und Frankfurter Ausgabe, vol. 21, p. 303.

- Stephanie LeMenager, Living oil. Petroleum culture in the American Century, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014.

- Rüdiger Graf, Öl und Souveränität. Petroknowledge und Energiepolitik in den USA und Westeuropa in den 1970er Jahren, Verlag Walter de Gruyter, 2017.

- American Book Review, „Petrofictions”, Vol. 33, Nr. 3, 2012.

Bitterfeld

24 June 1988, Saturday evening: people meet in a restaurant, and afterwards in a private home in Leipzig to forge a conspiracy. The participants include journalists Margit Miosga, Ulrich Neumann and Rainer Hällfritzsch, and Edgar Wallisch, a doctor with a politically motivated ban on practising his profession. The morning after, they depart late for their visit to Bitterfeld, the lignite and chemical site north of Halle. The group, en route in a black Lada, plans to make a documentary there. The camera and other filming materials were cleverly smuggled from West Berlin and were to be returned there after the shoot. In Bitterfeld, the group meets chemical worker Hans Zimmermann. With his help and local knowledge, they document the environmental damage in and around the city. They are aware of the risk that if their undertaking is discovered, they will be investigated and imprisoned. Nevertheless, their plan works.